Jan 7 2020

Jan 7 2020For Vancouver Island’s old-growth explorers, naming trees is a delight – but saving them is a challenge

Conservationist Ken Wu has chronicled B.C.’s ancient trees and given them catchy names, hoping it will build support to keep them standing. Now, the province faces crucial choices about logging, biodiversity, Indigenous rights and the fate of the forests.

The Globe and Mail

January 7th, 2020

San Juan Valley, Vancouver Island

/arc-anglerfish-tgam-prod-tgam.s3.amazonaws.com/public/CPL3BAEPMBAORDK3ZODTSHEVYU.JPG)

On a foggy day in November in the heart of a primeval forest, conservationist Ken Wu and biology graduate student Ian Thomas were standing at the base of a Sitka spruce, looking way up.

“Gaston!” Mr. Wu pronounced, pointing out the thick branches in the upper reaches of the 500-year-old tree, in which he sees the bicep-flexing character of his young daughter’s favourite Disney animation, Beauty and the Beast.

More than 80 years ago, in his collection of poems, Old Possum’s Book of Practical Cats, T.S. Eliot provided exacting instructions for the naming of cats. The conventions around the naming of ancient trees is a less complicated affair.

Mr. Wu, who heads the Endangered Ecosystems Alliance, hunts big trees and gives them nicknames, hoping to build public support for protecting some of the last remaining old-growth forests on Vancouver Island. His nicknames aim to be as catchy as an advertising jingle. “We don’t have the luxury to be boring,” he explains.

“It’s just a fun way to draw attention – in a viral way, hopefully – to a magnificent, endangered grove.” He named Big Lonely Doug, a Douglas fir that has been identified as the second-largest in Canada, which stands alone in the middle of a clear-cut. He helped win protection for nearby Avatar Grove so its trees would be spared the same fate.

/arc-anglerfish-tgam-prod-tgam.s3.amazonaws.com/public/U5CCKIUETZD2REP7ETDXNPFAIU.JPG)

These groves, spread out over roughly 500 hectares of the San Juan Valley floodplain, are largely unprotected. Two-thirds of the known old-growth forests here are on private forestry land, and one-third are on Crown land, within the operating area of BC Timber Sales.

The province has approved sections of land in the valley for logging, and Mr. Wu and Mr. Thomas are racing to catalog what they hope to save before the logging trucks roll in.

Forestry remains a major economic driver in British Columbia for many communities, and the provincial government is under pressure to protect the industry, which depends on a steady supply of both old- and second-growth logs to feed the province’s sawmills.

The tree Mr. Wu dubbed Gaston stands in a rugged section of Vancouver Island’s west coast. Sitka spruce are the largest in the world, and have been found reaching close to 100 metres in height next door in the Carmanah Valley. In these wet valleys on the edge of the Pacific Ocean, the trees thrive in a foggy, boggy micro-climate that incites fast growth.

Together, the pair have charted 22 similar groves on this floodplain that features trees no less than 250 years of age. Mr. Thomas, who ought to be finishing his thesis on bird song, has been distracted for weeks, scouring hectares of the valley bottom.

/arc-anglerfish-tgam-prod-tgam.s3.amazonaws.com/public/5GAIJB7U5ZGNLEPAFOHJ4GBKWY.JPG)

To visit some of these groves, we drive past the town of Port Renfrew (which bills itself as the Tall Tree Capital of Canada), eventually turning onto a rough and narrow gravel road. Then, on foot, we pick our way through a forest floor thick with giant sword ferns and lichen-draped salmonberries.

“I love these ecosystems, but it’s a hellish sort of bushwhack through a lot of it,” Mr. Wu warns.

This is what Mr. Wu refers to as the Serengeti of Vancouver Island’s rainforest: It is home to Roosevelt elk, black-tailed deer, wolves, cougars and black bears.

The easiest part of the hike is where the elk have broken a trail; their fresh hoofprints after the recent rain suggest we are following a busy thoroughfare.

The forest understory is quite unlike what is found in the region’s second-growth forests – there is a luscious disorder here, with branches draped in solid curtains of moss, trees growing out of the decay of fallen nurse logs. In one grove, a young hemlock tree grows up and into the side of a massive spruce. Perhaps one day it will take over the space.

It is not a wilderness – the Pacheedaht First Nation people have occupied these lands for thousands of years, and their ancient villages and campsites have been recorded up and down the San Juan river, an important spawning ground for chinook salmon and green sturgeon.

“Gaston” is growing about two kilometres east of a former summer fish camp near Fairy Lake. In these forests, the Pacheedaht have harvested red cedar to make long-houses, masks and canoes. Spruce roots were used to make rope, fishing line and thread.

Yet as we hack our way further into the forest, any hint of human intervention disappears. The vibe is very lost-in-time.

“This feels like a dinosaur should be stomping around,” Mr. Wu says.

These floodplains that nurture both old-growth Sitka spruce and salmonberries are rare, classified by the Ministry of Environment as “red-listed” ecosystems – endangered or threatened.

However, these trees could be up on the auction block at any moment. A large cedar here can be worth $50,000 to a logging company. The old giant Gaston would likely be destined for two-by-fours, if it ends up in a sawmill.

/arc-anglerfish-tgam-prod-tgam.s3.amazonaws.com/public/45B3RND34RBNZA6BMD2XY555BQ.JPG)

/arc-anglerfish-tgam-prod-tgam.s3.amazonaws.com/public/G3YYGGXO6BC43HFWSNAVB56JEE.JPG)

Today, B.C.’s provincial government, the New Democratic Party, is poised to make some critical decisions about the future of old growth.

Doug Donaldson, Minister of Forests, Lands and Natural Resource Operations and Rural Development, appointed an independent panel last summer to consult with British Columbians about how to manage old-growth forests.

The deadline for public response to a questionnaire is Jan. 31, and the panel’s recommendations are due back in the spring of 2020. When he announced the panel, Mr. Donaldson said in a statement that he is “committed to developing a new thoughtful and measured approach to managing this resource for the benefit of all British Columbians.”

Mr. Donaldson has also promised what he describes as significant amendments to the Forest and Range Practices Act, after his initial consultations showed strong public support to protect old growth forests.

But B.C. has yet to say how it will assist Canada in its commitment to meet its targets in a global effort to stem the tide of biodiversity loss.

The government is under intense pressure to keep logging. The B.C. forest sector is in crisis. Mills are closing as the timber supply shrinks and trade disputes drive up costs. The labour-friendly provincial government, now 2½ years into its current mandate, is wary of measures to curb logging and to date has offered few, and small, victories to conservationists.

/arc-anglerfish-tgam-prod-tgam.s3.amazonaws.com/public/DFCX3Z5TUBGFLJL37BIIOIBWSM.JPG)

In December, forest industry workers gathered on the front steps of the B.C. Legislature in Victoria to demand the government intervene in a months-long strike by 3,000 Western Forest Products employees on Vancouver Island.

Ron Tucker was among the protesters. A second generation logger who now owns his own small logging outfit, Mr. Tucker represents the dilemma for the government.

These workers come from NDP-held ridings. While ecologists such as Mr. Wu say the industry needs help to adapt to second-growth logging and more secondary manufacturing, the protesters say B.C. has already created enough protected areas.

“It would shut the forest industry down if you took old-growth logging out of the program,” Mr. Tucker said in an interview. He works in a tree farm licence on the north end of Vancouver Island where the harvest is one-fifth second growth, and four-fifths old growth.

“This industry is far too important for this province to lose. It is still the biggest economic driver in B.C. I mean, they’ve got new hospitals planned, and new schools planned, and all these big expenditures,” he said. “Without forestry, there’s no way that they can can do what they say they’re gonna do.”

The image of Big Lonely Doug does not sway Mr. Tucker and his colleagues, who just want to get back to work and meet their mortgage payments.

“I’m not gonna deny clearcuts are ugly. They are. And [conservationists] take pictures of this ugly clearcut and then basically go back to the general public and say this is what logging is. It’s so far from the truth. I’ve been in logging my whole life. I’m actually almost falling timber that was planted when I first started hauling logs.”

/arc-anglerfish-tgam-prod-tgam.s3.amazonaws.com/public/M226CQDEZNANNDASDT6RTHMHXQ.JPG)

Mr. Wu argues there is far more to be gained by leaving these forests intact. Old-growth forests can foster tourism and recreation jobs, while supporting endangered species, clean water, wild salmon and carbon sequestration to contribute to the battle against climate change.

His Endangered Ecosystems Alliance has called for a moratorium on logging of the most intact old-growth tracts. They want funding to establish Indigenous Protected Areas – tribal parks – that would allow local First Nations to manage the lands. And they want government to offer incentives and regulations to encourage the development of a value-added, second-growth forest industry so that people such as Mr. Tucker can still make a living, without threatening the biodiversity that depends on old-growth forests.

The Indigenous component would be critical to this, as many First Nations communities rely on forestry partnerships to build their own economies. That includes the Pacheedaht First Nation. In September, B.C.’s chief forester increased the amount of timber available to be harvested in this region, through Tree Farm Licence 61, because the forests are growing faster than estimated in the previous timber supply review. The Pacheedaht First Nation has a joint venture to log in TFL61, which includes 2,900 hectares of forests that are older than 240 years. Any new protected areas here will have to provide for the human well-being of the people who have traditionally occupied these lands.

/arc-anglerfish-tgam-prod-tgam.s3.amazonaws.com/public/V5DFQQ427ZEVPAJ3OB5QXIGUEU.JPG)

/arc-anglerfish-tgam-prod-tgam.s3.amazonaws.com/public/RFDLRSKNMNHIVATJ7ZOZEPTZKQ.JPG)

Mr. Wu’s quest for big trees along the San Juan river started eight years ago, when he was running the Avatar Grove campaign in the next valley over. He suspected there were some stands of old growth hidden in the mature second-growth forests, but he didn’t have time to explore.

It was Mr. Thomas, who happened to take a tour of old growth with Mr. Wu, who sparked the hunt. “I was blown away. It’s incredible this still exists,” Mr. Thomas said as we explored the valley. He started studying satellite maps of the San Juan Valley bottom to plan his next visit. “I wanted to check out all these groves when I should have been writing my thesis.”

For a biologist, the San Juan Valley floodplain is a gold mine of eco-diversity. Standing at the base of a 300-year-old tree, Mr. Thomas sees a natural sculpture that is impossible to replicate in a second-growth tree plantation. He points out where bats can roost, and how the massive roots that grew over a long-decayed nurse log have left an opening for a black bear’s den. A pine marten has retreated up the trunk to safety while we invade its turf. The diversity of form and function makes space for them all.

“We hit the big-tree jackpot here,” Mr. Wu says.

This year, the provincial government will decide whether it is a jackpot to be protected, or harvested.

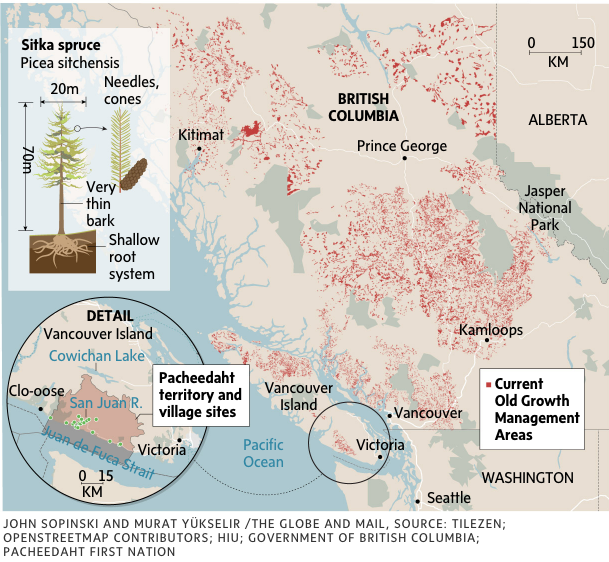

Overview: Where B.C.’s old forests grow

Some of Vancouver Island’s last old-growth forests can be found in the San Juan Valley floodplain, the traditional territory of the Pacheedaht people. Sitka spruce can grow to gigantic size there. But two-thirds of these forests are on private forestry land, and the rest on Crown land. Across B.C., Old Growth Management Areas protect ancient forests from development, but the province’s plan for safeguarding old-growth trees is now under review by an independent panel.

Read the original article

/arc-anglerfish-tgam-prod-tgam.s3.amazonaws.com/public/TBGWW7UOJREUNIQKZWTQQ3FJ7Q.JPG)